"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

03/31/2017 at 13:21 • Filed to: literary shitposting, also ordinary shitposting, dajnik, Longfellow

4

4

16

16

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

03/31/2017 at 13:21 • Filed to: literary shitposting, also ordinary shitposting, dajnik, Longfellow |  4 4

|  16 16 |

THE SHADES of night were falling fast,

As through an Alpine village passed

A youth, who bore, ‘mid snow and ice,

A banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

His brow was sad; his eye beneath,

Flashed like a falchion from its sheath,

And like a silver clarion rung

The accents of that unknown tongue,

Excelsior!

In happy homes he saw the light

Of household fires gleam warm and bright;

Above, the spectral glaciers shone,

And from his lips escaped a groan,

Excelsior!

“Try not the Pass!” the old man said;

“Dark lowers the tempest overhead,

The roaring torrent is deep and wide!”

And loud that clarion voice replied,

Excelsior!

“Oh, stay,” the maiden said, “and rest

Thy weary head upon this breast!”

A tear stood in his bright blue eye,

But still he answered, with a sigh,

Excelsior!

“Beware the pine-tree’s withered branch!

Beware the awful avalanche!”

This was the peasant’s last Good-night,

A voice replied, far up the height,

Excelsior!

At break of day, as heavenward

The pious monks of Saint Bernard

Uttered the oft-repeated prayer,

A voice cried through the startled air,

Excelsior!

A traveller, by the faithful hound,

Half-buried in the snow was found,

Still grasping in his hand of ice

That banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

There, in the twilight cold and gray,

Lifeless, but beautiful, he lay,

And from the sky, serene and far,

A voice fell, like a falling star,

Excelsior

lol “infinite scroll”

lol kinja

For Sweden

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

For Sweden

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:25 |

|

Infinite scroll = infinite content = infinite unique page views = infinite $$$ for capitalist Univision masters.

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> For Sweden

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> For Sweden

03/31/2017 at 13:27 |

|

I mean, if this post is going to get attached to the next few top posts, it might as well be hella long and classy as

fuck.

Xyl0c41n3

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

Xyl0c41n3

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:29 |

|

You need to warn a girl to be near her fainting couch before you go posting poetry on kinja, Rover. *fans self*

Also, endless scroll with endless “Read More” buttons. Sigh... seriously, whose bright idea was this?

If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:42 |

|

If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:44 |

|

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> Xyl0c41n3

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> Xyl0c41n3

03/31/2017 at 13:46 |

|

I seem to recall a scene in a P. G. Wodehouse where Bertie was trying to steel himself up for something and misremembering bits of Excelsior as part of it. Funny, but not quite as funny as enabling Edwin the Boy Scout into literally blowing up a small cottage.

I saw somebody crosspost a Kinja tech response that indicated the proper term for the bullshit was “infinite scroll”, which (at least so far) is pretty much The Dumbest Thing. It only loads the next five stories or whatever, which then runs their pageviews up, which makes them trend, which makes them appear at the bottom of the post again. Since, y’know, we’d like to click on them and read them right after we read them, dawg. DURRR

Hence giant wall o’ poetry. Tee hee.

If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:47 |

|

Quoth the Raven; “Excelsior”.

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> If only EssExTee could be so grossly incandescent

03/31/2017 at 13:47 |

|

iunderstoodthatreference.gif

Nibby

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

Nibby

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:48 |

|

A book has neither object nor subject; it is made of variously formed matters, and very different dates and speeds. To attribute the book to a subject is to overlook this working of matters, and the exteriority of their relations. It is to fabricate a beneficent God to explain geological movements. In a book, as in all things, there are lines of articulation or segmentarity, strata and territories; but also lines of flight, movements of deterritorialization and destratification. Comparative rates of flow on these lines produce phenomena of relative slowness and viscosity, or, on the contrary, of acceleration and rupture. All this, lines and measurable speeds, constitutes an assemblage. A book is an assemblage of this kind, and as such is unattributable. It is a multiplicity—but we don’t know yet what the multiple entails when it is no longer attributed, that is, after it has been elevated to the status of a substantive. One side of a machinic assemblage faces the strata, which doubtless make it a kind of organism, or signifying totality, or determination attributable to a subject; it also has a side facing a body without organs, which is continually dismantling the organism, causing asignifying particles or pure intensities to pass or circulate, and attributing to itself subjects that it leaves with nothing more than a name as the trace of an intensity. What is the body without organs of a book? There are several, depending on the nature of the lines considered, their particular grade or density, and the possibility of their converging on a “plane of consistency” assuring their selection. Here, as elsewhere, the units of measure are what is essential: quantify writing. There is no difference between what a book talks about and how it is made. Therefore a book also has no object. As an assemblage, a book has only itself, in connection with other assemblages and in relation to other bodies without organs. We will never ask what a book means, as signified or signifier; we will not look for anything to understand in it. We will ask what it functions with, in connection with what other things it does or does not transmit intensities, in which other multiplicities its own are inserted and metamorphosed, and with what bodies without organs it makes its own converge. A book exists only through the outside and on the outside. A book itself is a little machine; what is the relation (also measurable) of this literary machine to a war machine, love machine, revolutionary machine, etc.—and an abstract machine that sweeps them along? We have been criticized for overquoting literary authors. But when one writes, the only question is which other machine the literary machine can be plugged into, must be plugged into in order to work. Kleist and a mad war machine, Kafka and a most extraordinary bureaucratic machine . . . (What if one became animal or plant through literature, which certainly does not mean literarily? Is it not first through the voice that one becomes animal?) Literature is an assemblage. It has nothing to do with ideology. There is no ideology and never has been. All we talk about are multiplicities, lines, strata and segmentarities, lines of flight and intensities, machinic assemblages and their various types, bodies without organs and their construction and selection, the plane of consistency, and in each case the units of measure: Stratometers, deleometers, BwO units of density, BwO units of convergence: Not only dothese constitute a quantification of writing, but they define writing as always the measure of something else. Writing has nothing to do with signifying. It has to do with surveying, mapping, even realms that are yet to come.

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> Nibby

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> Nibby

03/31/2017 at 13:50 |

|

The

universe

(which

others

call

the

Library)

is

composed

of

an

indefinite

and

perhaps

infinite

number

of

hexagonal

galleries,

with

vast

air

shafts

between,

surrounded

by

very

low

railings.

From

any

of

the

hexagons

one

can

see,

interminably,

the

upper

and

lower

floors.

The

distribution

of

the

galleries

is

invariable.

Twenty

shelves,

five

long

shelves

per

side,

cover

all

the

sides

except

two;

their

height,

which

is

the

distance

from

floor

to

ceiling,

scarcely

exceeds

that

of

a

normal

bookcase.

One

of

the

free

sides

leads

to

a

narrow

hallway

which

opens

onto

another

gallery,

identical

to

the

first

and

to

all

the

rest.

To

the

left

and

right

of

the

hallway

there

are

two

very

small

closets.

In

the

first,

one

may

sleep

standing

up;

in

the

other,

satisfy

one’s

fecal

necessities.

Also

through

here

passes

a

spiral

stairway,

which

sinks

abysmally

and

soars

upwards

to

remote

distances.

In

the

hallway

there

is

a

mirror

which

faithfully

duplicates

all

appearances.

Men

usually

infer

from

this

mirror

that

the

Library

is

not

infinite

(if

it

were,

why

this

illusory

duplication?);

I

prefer

to

dream

that

its

polished

surfaces

represent

and

promise

the

infinite

...

Light

is

provided

by

some

spherical

fruit

which

bear

the

name

of

lamps.

There

are

two,

transversally

placed,

in

each

hexagon.

The

light

they

emit

is

insufficient, incessant

Like

all

men

of

the

Library,

I

have

traveled

in

my

youth;

I

have

wandered

in

search

of

a

book,

perhaps

the

catalogue

of

catalogues;

now

that

my

eyes

can

hardly

decipher

what

I

write,

I

am

preparing

to

die

just

a

few

leagues

from

the

hexagon

in

which

I

was

born.

Once

I

am

dead,

there

will

be

no

lack

of

pious

hands

to

throw

me

over

the

railing;

my

grave

will

be

the

fathomless

air;

my

body

will

sink

endlessly

and

decay

and

dissolve

in

the

wind

generated

by

the

fall,

which

is

infinite.

I

say

that

the

Library

is

unending.

The

idealists

argue

that

the

hexagonal

rooms

are

a

necessary

from

of

absolute

space

or,

at

least,

of

our

intuition

of

space.

They

reason

that

a

triangular

or

pentagonal

room

is

inconceivable.

(The

mystics

claim

that

their

ecstasy

reveals

to

them

a

circular

chamber

containing

a

great

circular

book,

whose

spine

is

continuous

and

which

follows

the

complete

circle

of

the

walls;

but

their

testimony

is

suspect;

their

words,

obscure.

This

cyclical

book

is

God.)

Let

it

suffice

now

for

me

to

repeat

the

classic

dictum:

The

Library

is

a

sphere

whose

exact

center

is

any

one

of

its

hexagons

and

whose circumference is inaccessible.

There

are

five

shelves

for

each

of

the

hexagon’s

walls;

each

shelf

contains

thirty-five

books

of

uniform

format;

each

book

is

of

four

hundred

and

ten

pages;

each

page,

of

forty

lines,

each

line,

of

some

eighty

letters

which

are

black

in

color.

There

are

also

letters

on

the

spine

of

each

book;

these

letters

do

not

indicate

or

prefigure

what

the

pages

will

say.

I

know

that

this

incoherence

at

one

time

seemed

mysterious.

Before

summarizing

the

solution

(whose

discovery,

in

spite

of

its

tragic

projections,

is

perhaps

the

capital

fact

in

history)

I

wish

to

recall a few axioms.

2

First:

The

Library

exists

ab

aeterno

.

This

truth,

whose

immediate

corollary

is

the

future

eternity

of

the

world,

cannot

be

placed

in

doubt

by

any

reasonable

mind.

Man,

the

imperfect

librarian,

may

be

the

product

of

chance

or

of

malevolent

demiurgi;

the

universe,

with

its

elegant

endowment

of

shelves,

of

enigmatical

volumes,

of

inexhaustible

stairways

for

the

traveler

and

latrines

for

the

seated

librarian,

can

only

be

the

work

of

a

god.

To

perceive

the

distance

between

the

divine

and

the

human,

it

is

enough

to

compare

these

crude

wavering

symbols

which

my

fallible

hand

scrawls

on

the

cover

of

a

book,

with

the

organic

letters

inside:

punctual, delicate, perfectly black, inimitably symmetrical.

Second:

The

orthographical

symbols

are

twenty-five

in

number.

(1)

This

finding

made

it

possible,

three

hundred

years

ago,

to

formulate

a

general

theory

of

the

Library

and

solve

satisfactorily

the

problem

which

no

conjecture

had

deciphered:

the

formless

and

chaotic

nature

of

almost

all

the

books.

One

which

my

father

saw

in

a

hexagon

on

circuit

fifteen

ninety-four

was

made

up

of

the

letters

MCV,

perversely

repeated

from

the

first

line

to

the

last.

Another

(very

much

consulted

in

this

area)

is

a

mere

labyrinth

of

letters,

but

the

next-to-

last

page

says

Oh

time

thy

pyramids.

This

much

is

already

known:

for

every

sensible

line

of

straightforward

statement,

there

are

leagues

of

senseless

cacophonies,

verbal

jumbles

and

incoherences.

(I

know

of

an

uncouth

region

whose

librarians

repudiate

the

vain

and

superstitious

custom

of

finding

a

meaning

in

books

and

equate

it

with

that

of

finding

a

meaning

in

dreams

or

in

the

chaotic

lines

of

one’s

palm

...

They

admit

that

the

inventors

of

this

writing

imitated

the

twenty-five

natural

symbols,

but

maintain

that

this

application

is

accidental

and

that

the

books

signify

nothing

in

themselves.

This

dictum,

we

shall

see,

is

not

entirely fallacious.)

For

a

long

time

it

was

believed

that

these

impenetrable

books

corresponded

to

past

or

remote

languages.

It

is

true

that

the

most

ancient

men,

the

first

librarians,

used

a

language

quite

different

from

the

one

we

now

speak;

it

is

true

that

a

few

miles

to

the

right

the

tongue

is

dialectical

and

that

ninety

floors

farther

up,

it

is

incomprehensible.

All

this,

I

repeat,

is

true,

but

four

hundred

and

ten

pages

of

inalterable

MCV’s

cannot

correspond

to

any

language,

no

matter

how

dialectical

or

rudimentary

it

may

be.

Some

insinuated

that

each

letter

could

influence

the

following

one

and

that

the

value

of

MCV

in

the

third

line

of

page

71

was

not

the

one

the

same

series

may

have

in

another

position

on

another

page,

but

this

vague

thesis

did

not

prevail.

Others

thought

of

cryptographs;

generally,

this

conjecture

has

been

accepted,

though not in the sense in which it was formulated by its originators.

Five

hundred

years

ago,

the

chief

of

an

upper

hexagon

(2)

came

upon

a

book

as

confusing

as

the

others,

but

which

had

nearly

two

pages

of

homogeneous

lines.

He

showed

his

find

to

a

wandering

decoder

who

told

him

the

lines

were

written

in

Portuguese;

others

said

they

were

Yiddish.

Within

a

century,

the

language

was

established:

a

Samoyedic

Lithuanian

dialect

of

Guarani,

with

classical

Arabian

inflections.

The

content

was

also

deciphered:

some

notions

of

combinative

analysis,

illustrated

with

examples

of

variations

with

unlimited

repetition.

These

examples

made

it

possible

for

a

librarian

of

genius

to

discover

the

fundamental

law

of

the

3

Library.

This

thinker

observed

that

all

the

books,

no

matter

how

diverse

they

might

be,

are

made

up

of

the

same

elements:

the

space,

the

period,

the

comma,

the

twenty-two

letters

of

the

alphabet.

He

also

alleged

a

fact

which

travelers

have

confirmed:

In

the

vast

Library

there

are

no

two

identical

books.

From

these

two

incontrovertible

premises

he

deduced

that

the

Library

is

total

and

that

its

shelves

register

all

the

possible

combinations

of

the

twenty-odd

orthographical

symbols

(a

number

which,

though

extremely

vast,

is

not

infinite):

Everything:

the

minutely

detailed

history

of

the

future,

the

archangels’

autobiographies,

the

faithful

catalogues

of

the

Library,

thousands

and

thousands

of

false

catalogues,

the

demonstration

of

the

fallacy

of

those

catalogues,

the

demonstration

of

the

fallacy

of

the

true

catalogue,

the

Gnostic

gospel

of

Basilides,

the

commentary

on

that

gospel,

the

commentary

on

the

commentary

on

that

gospel,

the

true

story

of

your

death,

the

translation

of

every

book

in

all

languages, the interpolations of every book in all books.

When

it

was

proclaimed

that

the

Library

contained

all

books,

the

first

impression

was

one

of

extravagant

happiness.

All

men

felt

themselves

to

be

the

masters

of

an

intact

and

secret

treasure.

There

was

no

personal

or

world

problem

whose

eloquent

solution

did

not

exist

in

some

hexagon.

The

universe

was

justified,

the

universe

suddenly

usurped

the

unlimited

dimensions

of

hope.

At

that

time

a

great

deal

was

said

about

the

Vindications:

books

of

apology

and

prophecy

which

vindicated

for

all

time

the

acts

of

every

man

in

the

universe

and

retained

prodigious

arcana

for

his

future.

Thousands

of

the

greedy

abandoned

their

sweet

native

hexagons

and

rushed

up

the

stairways,

urged

on

by

the

vain

intention

of

finding

their

Vindication.

These

pilgrims

disputed

in

the

narrow

corridors,

proferred

dark

curses,

strangled

each

other

on

the

divine

stairways,

flung

the

deceptive

books

into

the

air

shafts,

met

their

death

cast

down

in

a

similar

fashion

by

the

inhabitants

of

remote

regions.

Others

went

mad

...

The

Vindications

exist

(I

have

seen

two

which

refer

to

persons

of

the

future,

to

persons

who

are

perhaps

not

imaginary)

but

the

searchers

did

not

remember

that

the

possibility

of

a

man’s

finding

his

Vindication,

or

some

treacherous

variation

thereof,

can

be

computed as zero.

At

that

time

it

was

also

hoped

that

a

clarification

of

humanity’s

basic

mysteries

—

the

origin

of

the

Library

and

of

time

—

might

be

found.

It

is

verisimilar

that

these

grave

mysteries

could

be

explained

in

words:

if

the

language

of

philosophers

is

not

sufficient,

the

multiform

Library

will

have

produced

the

unprecedented

language

required,

with

its

vocabularies

and

grammars.

For

four

centuries

now

men

have

exhausted

the

hexagons

...

There

are

official

searchers,

inquisitors.

I

have

seen

them

in

the

performance

of

their

function:

they

always

arrive

extremely

tired

from

their

journeys;

they

speak

of

a

broken

stairway

which

almost

killed

them;

they

talk

with

the

librarian

of

galleries

and

stairs;

sometimes

they

pick

up

the

nearest

volume

and

leaf

through

it,

looking

for

infamous

words.

Obviously,

no

one

expects

to

discover anything.

As

was

natural,

this

inordinate

hope

was

followed

by

an

excessive

depression.

The

certitude

that

some

shelf

in

some

hexagon

held

precious

books

and

that

these

precious

books

were

inaccessible,

seemed

almost

intolerable.

A

blasphemous

sect

suggested

that

the

searches

4

should

cease

and

that

all

men

should

juggle

letters

and

symbols

until

they

constructed,

by

an

improbable

gift

of

chance,

these

canonical

books.

The

authorities

were

obliged

to

issue

severe

orders.

The

sect

disappeared,

but

in

my

childhood

I

have

seen

old

men

who,

for

long

periods

of

time,

would

hide

in

the

latrines

with

some

metal

disks

in

a

forbidden

dice

cup

and

feebly

mimic the divine disorder.

Others,

inversely,

believed

that

it

was

fundamental

to

eliminate

useless

works.

They

invaded

the

hexagons,

showed

credentials

which

were

not

always

false,

leafed

through

a

volume

with

displeasure

and

condemned

whole

shelves:

their

hygienic,

ascetic

furor

caused

the

senseless

perdition

of

millions

of

books.

Their

name

is

execrated,

but

those

who

deplore

the

``treasures’’

destroyed

by

this

frenzy

neglect

two

notable

facts.

One:

the

Library

is

so

enormous

that

any

reduction

of

human

origin

is

infinitesimal.

The

other:

every

copy

is

unique,

irreplaceable,

but

(since

the

Library

is

total)

there

are

always

several

hundred

thousand

imperfect

facsimiles:

works

which

differ

only

in

a

letter

or

a

comma.

Counter

to

general

opinion,

I

venture

to

suppose

that

the

consequences

of

the

Purifiers’

depredations

have

been

exaggerated

by

the

horror

these

fanatics

produced.

They

were

urged

on

by

the

delirium

of

trying

to

reach

the

books

in

the

Crimson

Hexagon:

books

whose

format

is

smaller

than usual, all-powerful, illustrated and magical.

We

also

know

of

another

superstition

of

that

time:

that

of

the

Man

of

the

Book.

On

some

shelf

in

some

hexagon

(men

reasoned)

there

must

exist

a

book

which

is

the

formula

and

perfect

compendium

of

all

the

rest:

some

librarian

has

gone

through

it

and

he

is

analogous

to

a

god.

In

the

language

of

this

zone

vestiges

of

this

remote

functionary’s

cult

still

persist.

Many

wandered

in

search

of

Him.

For

a

century

they

have

exhausted

in

vain

the

most

varied

areas.

How

could

one

locate

the

venerated

and

secret

hexagon

which

housed

Him?

Someone

proposed

a

regressive

method:

To

locate

book

A,

consult

first

book

B

which

indicates

A’s

position;

to

locate

book

B,

consult

first

a

book

C,

and

so

on

to

infinity

...

In

adventures

such

as

these,

I

have

squandered

and

wasted

my

years.

It

does

not

seem

unlikely

to

me

that

there

is

a

total

book

on

some

shelf

of

the

universe;

(3)

I

pray

to

the

unknown

gods

that

a

man

—

just

one,

even

though

it

were

thousands

of

years

ago!

—

may

have

examined

and

read

it.

If

honor

and

wisdom

and

happiness

are

not

for

me,

let

them

be

for

others.

Let

heaven

exist,

though

my

place

be

in

hell.

Let

me

be

outraged

and

annihilated,

but

for

one

instant,

in

one

being,

let

Your

enormous

Library

be

justified.

The

impious

maintain

that

nonsense

is

normal

in

the

Library

and

that

the

reasonable

(and

even

humble

and

pure

coherence)

is

an

almost

miraculous

exception.

They

speak

(I

know)

of

the

``feverish

Library

whose

chance

volumes

are

constantly

in

danger

of

changing

into

others

and

affirm,

negate

and

confuse

everything

like

a

delirious

divinity.’’

These

words,

which

not

only

denounce

the

disorder

but

exemplify

it

as

well,

notoriously

prove

their

authors’

abominable

taste

and

desperate

ignorance.

In

truth,

the

Library

includes

all

verbal

structures,

all

variations

permitted

by

the

twenty-five

orthographical

symbols,

but

not

a

single

example

of

absolute

nonsense.

It

is

useless

to

observe

that

the

best

volume

of

the

many

hexagons

under

my

administration

is

entitled

The

Combed

Thunderclap

and

another

The

Plaster

Cramp

and

another

Axaxaxas

mlö.

These

phrases,

at

first

glance

incoherent,

can

no

doubt

be

justified

in

a

cryptographical

or

allegorical

manner;

5

such

a

justification

is

verbal

and,

ex

hypothesi,

already

figures

in

the

Library.

I

cannot

combine some characters

d

h

c

m

r

l

c

h

t

d

j

which

the

divine

Library

has

not

foreseen

and

which

in

one

of

its

secret

tongues

do

not

contain

a

terrible

meaning.

No

one

can

articulate

a

syllable

which

is

not

filled

with

tenderness

and

fear,

which

is

not,

in

one

of

these

languages,

the

powerful

name

of

a

god.

To

speak

is

to

fall

into

tautology.

This

wordy

and

useless

epistle

already

exists

in

one

of

the

thirty

volumes

of

the

five

shelves

of

one

of

the

innumerable

hexagons

—

and

its

refutation

as

well.

(An

n

number

of

possible

languages

use

the

same

vocabulary;

in

some

of

them,

the

symbol

library

allows

the

correct

definition

a

ubiquitous

and

lasting

system

of

hexagonal

galleries,

but

library

is

bread

or

pyramid

or

anything

else,

and

these

seven

words

which

define

it

have

another

value. You who read me, are You sure of understanding my language?)

The

methodical

task

of

writing

distracts

me

from

the

present

state

of

men.

The

certitude

that

everything

has

been

written

negates

us

or

turns

us

into

phantoms.

I

know

of

districts

in

which

the

young

men

prostrate

themselves

before

books

and

kiss

their

pages

in

a

barbarous

manner,

but

they

do

not

know

how

to

decipher

a

single

letter.

Epidemics,

heretical

conflicts,

peregrinations

which

inevitably

degenerate

into

banditry,

have

decimated

the

population.

I

believe

I

have

mentioned

suicides,

more

and

more

frequent

with

the

years.

Perhaps

my

old

age

and

fearfulness

deceive

me,

but

I

suspect

that

the

human

species

—

the

unique

species

—

is

about

to

be

extinguished,

but

the

Library

will

endure:

illuminated,

solitary,

infinite,

perfectly motionless, equipped with precious volumes, useless, incorruptible, secret.

I

have

just

written

the

word

``infinite.’’

I

have

not

interpolated

this

adjective

out

of

rhetorical

habit;

I

say

that

it

is

not

illogical

to

think

that

the

world

is

infinite.

Those

who

judge

it

to

be

limited

postulate

that

in

remote

places

the

corridors

and

stairways

and

hexagons

can

conceivably

come

to

an

end

—

which

is

absurd.

Those

who

imagine

it

to

be

without

limit

forget

that

the

possible

number

of

books

does

have

such

a

limit.

I

venture

to

suggest

this

solution

to

the

ancient

problem:

The

Library

is

unlimited

and

cyclical.

If

an

eternal

traveler

were

to

cross

it

in

any

direction,

after

centuries

he

would

see

that

the

same

volumes

were

repeated

in

the

same

disorder

(which,

thus

repeated,

would

be

an

order:

the

Order).

My

solitude is gladdened by this elegant ho

Like

all

men

of

the

Library,

I

have

traveled

in

my

youth;

I

have

wandered

in

search

of

a

book,

perhaps

the

catalogue

of

catalogues;

now

that

my

eyes

can

hardly

decipher

what

I

write,

I

am

preparing

to

die

just

a

few

leagues

from

the

hexagon

in

which

I

was

born.

Once

I

am

dead,

there

will

be

no

lack

of

pious

hands

to

throw

me

over

the

railing;

my

grave

will

be

the

fathomless

air;

my

body

will

sink

endlessly

and

decay

and

dissolve

in

the

wind

generated

by

the

fall,

which

is

infinite.

I

say

that

the

Library

is

unending.

The

idealists

argue

that

the

hexagonal

rooms

are

a

necessary

from

of

absolute

space

or,

at

least,

of

our

intuition

of

space.

They

reason

that

a

triangular

or

pentagonal

room

is

inconceivable.

(The

mystics

claim

that

their

ecstasy

reveals

to

them

a

circular

chamber

containing

a

great

circular

book,

whose

spine

is

continuous

and

which

follows

the

complete

circle

of

the

walls;

but

their

testimony

is

suspect;

their

words,

obscure.

This

cyclical

book

is

God.)

Let

it

suffice

now

for

me

to

repeat

the

classic

dictum:

The

Library

is

a

sphere

whose

exact

center

is

any

one

of

its

hexagons

and

whose circumference is inaccessible.

There

are

five

shelves

for

each

of

the

hexagon’s

walls;

each

shelf

contains

thirty-five

books

of

uniform

format;

each

book

is

of

four

hundred

and

ten

pages;

each

page,

of

forty

lines,

each

line,

of

some

eighty

letters

which

are

black

in

color.

There

are

also

letters

on

the

spine

of

each

book;

these

letters

do

not

indicate

or

prefigure

what

the

pages

will

say.

I

know

that

this

incoherence

at

one

time

seemed

mysterious.

Before

summarizing

the

solution

(whose

discovery,

in

spite

of

its

tragic

projections,

is

perhaps

the

capital

fact

in

history)

I

wish

to

recall a few axioms.

2

First:

The

Library

exists

ab

aeterno

.

This

truth,

whose

immediate

corollary

is

the

future

eternity

of

the

world,

cannot

be

placed

in

doubt

by

any

reasonable

mind.

Man,

the

imperfect

librarian,

may

be

the

product

of

chance

or

of

malevolent

demiurgi;

the

universe,

with

its

elegant

endowment

of

shelves,

of

enigmatical

volumes,

of

inexhaustible

stairways

for

the

traveler

and

latrines

for

the

seated

librarian,

can

only

be

the

work

of

a

god.

To

perceive

the

distance

between

the

divine

and

the

human,

it

is

enough

to

compare

these

crude

wavering

symbols

which

my

fallible

hand

scrawls

on

the

cover

of

a

book,

with

the

organic

letters

inside:

punctual, delicate, perfectly black, inimitably symmetrical.

Second:

The

orthographical

symbols

are

twenty-five

in

number.

(1)

This

finding

made

it

possible,

three

hundred

years

ago,

to

formulate

a

general

theory

of

the

Library

and

solve

satisfactorily

the

problem

which

no

conjecture

had

deciphered:

the

formless

and

chaotic

nature

of

almost

all

the

books.

One

which

my

father

saw

in

a

hexagon

on

circuit

fifteen

ninety-four

was

made

up

of

the

letters

MCV,

perversely

repeated

from

the

first

line

to

the

last.

Another

(very

much

consulted

in

this

area)

is

a

mere

labyrinth

of

letters,

but

the

next-to-

last

page

says

Oh

time

thy

pyramids.

This

much

is

already

known:

for

every

sensible

line

of

straightforward

statement,

there

are

leagues

of

senseless

cacophonies,

verbal

jumbles

and

incoherences.

(I

know

of

an

uncouth

region

whose

librarians

repudiate

the

vain

and

superstitious

custom

of

finding

a

meaning

in

books

and

equate

it

with

that

of

finding

a

meaning

in

dreams

or

in

the

chaotic

lines

of

one’s

palm

...

They

admit

that

the

inventors

of

this

writing

imitated

the

twenty-five

natural

symbols,

but

maintain

that

this

application

is

accidental

and

that

the

books

signify

nothing

in

themselves.

This

dictum,

we

shall

see,

is

not

entirely fallacious.)

For

a

long

time

it

was

believed

that

these

impenetrable

books

corresponded

to

past

or

remote

languages.

It

is

true

that

the

most

ancient

men,

the

first

librarians,

used

a

language

quite

different

from

the

one

we

now

speak;

it

is

true

that

a

few

miles

to

the

right

the

tongue

is

dialectical

and

that

ninety

floors

farther

up,

it

is

incomprehensible.

All

this,

I

repeat,

is

true,

but

four

hundred

and

ten

pages

of

inalterable

MCV’s

cannot

correspond

to

any

language,

no

matter

how

dialectical

or

rudimentary

it

may

be.

Some

insinuated

that

each

letter

could

influence

the

following

one

and

that

the

value

of

MCV

in

the

third

line

of

page

71

was

not

the

one

the

same

series

may

have

in

another

position

on

another

page,

but

this

vague

thesis

did

not

prevail.

Others

thought

of

cryptographs;

generally,

this

conjecture

has

been

accepted,

though not in the sense in which it was formulated by its originators.

Five

hundred

years

ago,

the

chief

of

an

upper

hexagon

(2)

came

upon

a

book

as

confusing

as

the

others,

but

which

had

nearly

two

pages

of

homogeneous

lines.

He

showed

his

find

to

a

wandering

decoder

who

told

him

the

lines

were

written

in

Portuguese;

others

said

they

were

Yiddish.

Within

a

century,

the

language

was

established:

a

Samoyedic

Lithuanian

dialect

of

Guarani,

with

classical

Arabian

inflections.

The

content

was

also

deciphered:

some

notions

of

combinative

analysis,

illustrated

with

examples

of

variations

with

unlimited

repetition.

These

examples

made

it

possible

for

a

librarian

of

genius

to

discover

the

fundamental

law

of

the

3

Library.

This

thinker

observed

that

all

the

books,

no

matter

how

diverse

they

might

be,

are

made

up

of

the

same

elements:

the

space,

the

period,

the

comma,

the

twenty-two

letters

of

the

alphabet.

He

also

alleged

a

fact

which

travelers

have

confirmed:

In

the

vast

Library

there

are

no

two

identical

books.

From

these

two

incontrovertible

premises

he

deduced

that

the

Library

is

total

and

that

its

shelves

register

all

the

possible

combinations

of

the

twenty-odd

orthographical

symbols

(a

number

which,

though

extremely

vast,

is

not

infinite):

Everything:

the

minutely

detailed

history

of

the

future,

the

archangels’

autobiographies,

the

faithful

catalogues

of

the

Library,

thousands

and

thousands

of

false

catalogues,

the

demonstration

of

the

fallacy

of

those

catalogues,

the

demonstration

of

the

fallacy

of

the

true

catalogue,

the

Gnostic

gospel

of

Basilides,

the

commentary

on

that

gospel,

the

commentary

on

the

commentary

on

that

gospel,

the

true

story

of

your

death,

the

translation

of

every

book

in

all

languages, the interpolations of every book in all books.

When

it

was

proclaimed

that

the

Library

contained

all

books,

the

first

impression

was

one

of

extravagant

happiness.

All

men

felt

themselves

to

be

the

masters

of

an

intact

and

secret

treasure.

There

was

no

personal

or

world

problem

whose

eloquent

solution

did

not

exist

in

some

hexagon.

The

universe

was

justified,

the

universe

suddenly

usurped

the

unlimited

dimensions

of

hope.

At

that

time

a

great

deal

was

said

about

the

Vindications:

books

of

apology

and

prophecy

which

vindicated

for

all

time

the

acts

of

every

man

in

the

universe

and

retained

prodigious

arcana

for

his

future.

Thousands

of

the

greedy

abandoned

their

sweet

native

hexagons

and

rushed

up

the

stairways,

urged

on

by

the

vain

intention

of

finding

their

Vindication.

These

pilgrims

disputed

in

the

narrow

corridors,

proferred

dark

curses,

strangled

each

other

on

the

divine

stairways,

flung

the

deceptive

books

into

the

air

shafts,

met

their

death

cast

down

in

a

similar

fashion

by

the

inhabitants

of

remote

regions.

Others

went

mad

...

The

Vindications

exist

(I

have

seen

two

which

refer

to

persons

of

the

future,

to

persons

who

are

perhaps

not

imaginary)

but

the

searchers

did

not

remember

that

the

possibility

of

a

man’s

finding

his

Vindication,

or

some

treacherous

variation

thereof,

can

be

computed as zero.

At

that

time

it

was

also

hoped

that

a

clarification

of

humanity’s

basic

mysteries

—

the

origin

of

the

Library

and

of

time

—

might

be

found.

It

is

verisimilar

that

these

grave

mysteries

could

be

explained

in

words:

if

the

language

of

philosophers

is

not

sufficient,

the

multiform

Library

will

have

produced

the

unprecedented

language

required,

with

its

vocabularies

and

grammars.

For

four

centuries

now

men

have

exhausted

the

hexagons

...

There

are

official

searchers,

inquisitors.

I

have

seen

them

in

the

performance

of

their

function:

they

always

arrive

extremely

tired

from

their

journeys;

they

speak

of

a

broken

stairway

which

almost

killed

them;

they

talk

with

the

librarian

of

galleries

and

stairs;

sometimes

they

pick

up

the

nearest

volume

and

leaf

through

it,

looking

for

infamous

words.

Obviously,

no

one

expects

to

discover anything.

As

was

natural,

this

inordinate

hope

was

followed

by

an

excessive

depression.

The

certitude

that

some

shelf

in

some

hexagon

held

precious

books

and

that

these

precious

books

were

inaccessible,

seemed

almost

intolerable.

A

blasphemous

sect

suggested

that

the

searches

4

should

cease

and

that

all

men

should

juggle

letters

and

symbols

until

they

constructed,

by

an

improbable

gift

of

chance,

these

canonical

books.

The

authorities

were

obliged

to

issue

severe

orders.

The

sect

disappeared,

but

in

my

childhood

I

have

seen

old

men

who,

for

long

periods

of

time,

would

hide

in

the

latrines

with

some

metal

disks

in

a

forbidden

dice

cup

and

feebly

mimic the divine disorder.

Others,

inversely,

believed

that

it

was

fundamental

to

eliminate

useless

works.

They

invaded

the

hexagons,

showed

credentials

which

were

not

always

false,

leafed

through

a

volume

with

displeasure

and

condemned

whole

shelves:

their

hygienic,

ascetic

furor

caused

the

senseless

perdition

of

millions

of

books.

Their

name

is

execrated,

but

those

who

deplore

the

``treasures’’

destroyed

by

this

frenzy

neglect

two

notable

facts.

One:

the

Library

is

so

enormous

that

any

reduction

of

human

origin

is

infinitesimal.

The

other:

every

copy

is

unique,

irreplaceable,

but

(since

the

Library

is

total)

there

are

always

several

hundred

thousand

imperfect

facsimiles:

works

which

differ

only

in

a

letter

or

a

comma.

Counter

to

general

opinion,

I

venture

to

suppose

that

the

consequences

of

the

Purifiers’

depredations

have

been

exaggerated

by

the

horror

these

fanatics

produced.

They

were

urged

on

by

the

delirium

of

trying

to

reach

the

books

in

the

Crimson

Hexagon:

books

whose

format

is

smaller

than usual, all-powerful, illustrated and magical.

We

also

know

of

another

superstition

of

that

time:

that

of

the

Man

of

the

Book.

On

some

shelf

in

some

hexagon

(men

reasoned)

there

must

exist

a

book

which

is

the

formula

and

perfect

compendium

of

all

the

rest:

some

librarian

has

gone

through

it

and

he

is

analogous

to

a

god.

In

the

language

of

this

zone

vestiges

of

this

remote

functionary’s

cult

still

persist.

Many

wandered

in

search

of

Him.

For

a

century

they

have

exhausted

in

vain

the

most

varied

areas.

How

could

one

locate

the

venerated

and

secret

hexagon

which

housed

Him?

Someone

proposed

a

regressive

method:

To

locate

book

A,

consult

first

book

B

which

indicates

A’s

position;

to

locate

book

B,

consult

first

a

book

C,

and

so

on

to

infinity

...

In

adventures

such

as

these,

I

have

squandered

and

wasted

my

years.

It

does

not

seem

unlikely

to

me

that

there

is

a

total

book

on

some

shelf

of

the

universe;

(3)

I

pray

to

the

unknown

gods

that

a

man

—

just

one,

even

though

it

were

thousands

of

years

ago!

—

may

have

examined

and

read

it.

If

honor

and

wisdom

and

happiness

are

not

for

me,

let

them

be

for

others.

Let

heaven

exist,

though

my

place

be

in

hell.

Let

me

be

outraged

and

annihilated,

but

for

one

instant,

in

one

being,

let

Your

enormous

Library

be

justified.

The

impious

maintain

that

nonsense

is

normal

in

the

Library

and

that

the

reasonable

(and

even

humble

and

pure

coherence)

is

an

almost

miraculous

exception.

They

speak

(I

know)

of

the

``feverish

Library

whose

chance

volumes

are

constantly

in

danger

of

changing

into

others

and

affirm,

negate

and

confuse

everything

like

a

delirious

divinity.’’

These

words,

which

not

only

denounce

the

disorder

but

exemplify

it

as

well,

notoriously

prove

their

authors’

abominable

taste

and

desperate

ignorance.

In

truth,

the

Library

includes

all

verbal

structures,

all

variations

permitted

by

the

twenty-five

orthographical

symbols,

but

not

a

single

example

of

absolute

nonsense.

It

is

useless

to

observe

that

the

best

volume

of

the

many

hexagons

under

my

administration

is

entitled

The

Combed

Thunderclap

and

another

The

Plaster

Cramp

and

another

Axaxaxas

mlö.

These

phrases,

at

first

glance

incoherent,

can

no

doubt

be

justified

in

a

cryptographical

or

allegorical

manner;

5

such

a

justification

is

verbal

and,

ex

hypothesi,

already

figures

in

the

Library.

I

cannot

combine some characters

d

h

c

m

r

l

c

h

t

d

j

which

the

divine

Library

has

not

foreseen

and

which

in

one

of

its

secret

tongues

do

not

contain

a

terrible

meaning.

No

one

can

articulate

a

syllable

which

is

not

filled

with

tenderness

and

fear,

which

is

not,

in

one

of

these

languages,

the

powerful

name

of

a

god.

To

speak

is

to

fall

into

tautology.

This

wordy

and

useless

epistle

already

exists

in

one

of

the

thirty

volumes

of

the

five

shelves

of

one

of

the

innumerable

hexagons

—

and

its

refutation

as

well.

(An

n

number

of

possible

languages

use

the

same

vocabulary;

in

some

of

them,

the

symbol

library

allows

the

correct

definition

a

ubiquitous

and

lasting

system

of

hexagonal

galleries,

but

library

is

bread

or

pyramid

or

anything

else,

and

these

seven

words

which

define

it

have

another

value. You who read me, are You sure of understanding my language?)

The

methodical

task

of

writing

distracts

me

from

the

present

state

of

men.

The

certitude

that

everything

has

been

written

negates

us

or

turns

us

into

phantoms.

I

know

of

districts

in

which

the

young

men

prostrate

themselves

before

books

and

kiss

their

pages

in

a

barbarous

manner,

but

they

do

not

know

how

to

decipher

a

single

letter.

Epidemics,

heretical

conflicts,

peregrinations

which

inevitably

degenerate

into

banditry,

have

decimated

the

population.

I

believe

I

have

mentioned

suicides,

more

and

more

frequent

with

the

years.

Perhaps

my

old

age

and

fearfulness

deceive

me,

but

I

suspect

that

the

human

species

—

the

unique

species

—

is

about

to

be

extinguished,

but

the

Library

will

endure:

illuminated,

solitary,

infinite,

perfectly motionless, equipped with precious volumes, useless, incorruptible, secret.

I

have

just

written

the

word

``infinite.’’

I

have

not

interpolated

this

adjective

out

of

rhetorical

habit;

I

say

that

it

is

not

illogical

to

think

that

the

world

is

infinite.

Those

who

judge

it

to

be

limited

postulate

that

in

remote

places

the

corridors

and

stairways

and

hexagons

can

conceivably

come

to

an

end

—

which

is

absurd.

Those

who

imagine

it

to

be

without

limit

forget

that

the

possible

number

of

books

does

have

such

a

limit.

I

venture

to

suggest

this

solution

to

the

ancient

problem:

The

Library

is

unlimited

and

cyclical.

If

an

eternal

traveler

were

to

cross

it

in

any

direction,

after

centuries

he

would

see

that

the

same

volumes

were

repeated

in

the

same

disorder

(which,

thus

repeated,

would

be

an

order:

the

Order).

My

solitude is gladdened by this elegant hope

RallyWrench

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

RallyWrench

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:52 |

|

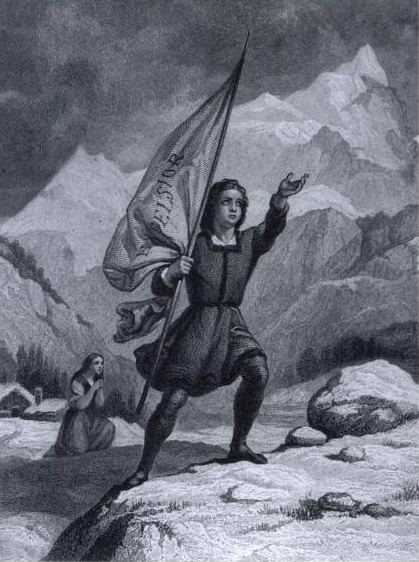

Tempest

Over Excelsior

Damn right I’d hang on to this in a roaring torrent.

Nibby

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

Nibby

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/31/2017 at 13:54 |

|

It is clear that the world is purely parodic, in other words, that each thing seen is the parody of another, or is the same thing in a deceptive form.

Ever since sentences started to circulate in brains devoted to reflection, an effort at total identification has been made, because with the aid of a copula each sentence ties one thing to another; all things would be visibly connected if one could discover at a single glance and in its totality the tracings of Ariadne’s thread leading thought into its own labyrinth.

But the copula of terms is no less irritating than the copulation of bodies. And when I scream I AM THE SUN an integral erection results, because the verb to be is the vehicle of amorous frenzy.

Everyone is aware that life is parodic and that it lacks an interpretation. Thus lead is the parody of gold. Air is the parody of water. The brain is the parody of the equator. Coitus is the parody of crime.

Gold, water, the equator, or crime can each be put forward as the principle of things.

And if the origin of things is not like the ground of the planet that seems to be the base, but like the circular movement that the planet describes around a mobile center, then a car, a clock, or a sewing machine could equally be accepted as the generative principle.

The two primary motions are rotation and sexual movement, whose combination is expressed by the locomotive’s wheels and pistons.

These two motions are reciprocally transformed, the one into the other.

Thus one notes that the earth, by turning, makes animals and men have coitus, and (because the result is as much the cause as that which provokes it) that animals and men make the earth turn by having coitus.

It is the mechanical combination or transformation of these movements that the alchemists sought as the philosopher’s stone.

It is through the use of this magically valued combination that one can determine the present position of men in the midst of the elements.

An abandoned shoe, a rotten tooth, a snub nose, the cook spitting in the soup of his masters are to love what a battle flag is to nationality.

An umbrella, a sexagenarian, a seminarian, the smell of rotten eggs, the hollow eyes of judges are the roots that nourish love.

A dog devouring the stomach of a goose, a drunken vomiting woman, a slobbering accountant, a jar of mustard represent the confusion that serves as the vehicle of love.

A man who finds himself among others is irritated because he does not know why he is not one of the others.

In bed next to a girl he loves, he forgets that he does not know why he is himself instead of the body he touches.

Without knowing it, he suffers from the mental darkness that keeps him from screaming that he himself is the girl who forgets his presence while shuddering in his arms.

Love or infantile rage, or a provincial dowager’s vanity, or clerical pornography, or the diamond of a soprano bewilder individuals forgotten in dusty apartments.

They can very well try to find each other; they will never find anything but parodic images, and they will fall asleep as empty as mirrors.

The absent and inert girl hanging dreamless from my arms is no more foreign to me than the door or window through which I can look or pass.

I rediscover indifference (allowing her to leave me) when I fall asleep, through an inability to love what happens.

It is impossible for her to know whom she will discover when I hold her, because she obstinately attains a complete forgetting.

The planetary systems that turn in space like rapid disks, and whose centers also move, describing an infinitely larger circle, only move away continuously from their own position in order to return it, completing their rotation.

Movement is a figure of love, incapable of stopping at a particular being, and rapidly passing from one to another.

But the forgetting that determines it in this way is only a subterfuge of memory.

A man gets up as brusquely as a specter in a coffin and falls in the same way.

He gets up a few hours later and then he falls again, and the same thing happens every day; this great coitus with the celestial atmosphere is regulated by the terrestrial rotation around the sun.

Thus even though terrestrial life moves to the rhythm of this rotation, the image of this movement is not turning earth, but the male shaft penetrating the female and almost entirely emerging, in order to reenter.

Love and life appear to be separate only because everything on earth is broken apart by vibrations of various amplitudes and durations.

However, there are no vibrations that are not conjugated with a continuous circular movement; in the same way, a locomotive rolling on the surface of the earth is the image of continuous metamorphosis.

Beings only die to be born, in the manner of phalluses that leave bodies in order to enter them.

Plants rise in the direction of the sun and then collapse in the direction of the ground.

Trees bristle the ground with a vast quantity of flowered shafts raised up to the sun.

The trees that forcefully soar end up burned by lightning, chopped down, or uprooted. Returned to the ground, they come back up in another form.